Almost a year ago to date, I published this piece in the Cooper Point Journal. Here is a short essay on the little events that lead up to it and followed it, the many continued layers that our work lives within, and is borne from.

A year ago, I was working for the Evergreen State College’s Writing Center, as a peer writing tutor. For Black History Month, we were to watch a film on the history of white supremacy. For a state college with a very liberal reputation, lying in the womb of grunge (Olympia, WA), Evergreen has a heavy police presence: It’s common to see fully armed police officers, unmarked cars, and an ever-increasing number of private security services on campus. We all are cognizant, in a tense, compartmentalized way, that these forces are in direct contradiction to the progressive Evergreen package, with its Audre Lorde quotes, MLK photos, posters listing the 10 elements of fascism, coveted gender-neutral bathrooms, and a workspace where we can use our preferred pronouns. It’s hard not to feel gaslit when the school insists on police presence at its Social Justice Center, alongside constant offers of mental health support and meditation practices– in lieu of making the campus actually safer and more liberatory.

I still believe in public education, and in public service, but Dang– it has tried me.

So, we watched this film. I know lots of people, especially white and privileged people, need to watch these films. I don’t consider myself past watching these films; I am also a person who watches a film like this, and gets a ptsd reaction: shaking, becoming non-verbal, my tongue tingling and going dry, my vision tunnels. I took the next day off of work, using my sick time, accrued through so many days and hours doing something I loved with a group of people I loved, serving a community I loved, within a thorny cage of an administration that cared so little about us.

Pretty much all of public service is like this.

So I sat in my shed and wrote this piece in a day and a half, with minimal editing. I then submitted it to the illustrious, amazing, wonderful, Cooper Point Journal, and they printed it. Our journal was the only place it belonged, where these words could truly be vibrant and alive with meaning. While my public service jobs have always been trying, I also get to have some good days. I felt like I was getting shot out of a cannon: buoyed by fireworks, thinking I might scatter to the ground down there somewhere, but, for now–very happy. I knew I might get fired. My coworker and I joked “no one reads the CPJ anyway”. Then people started to come up to me– many, many people: some acquaintances, some I didn’t expect, moms in my classes, library staff who were theoretically above me in the thorny cage chain, writers who I had tutored, and absolute randos. They all just said thank you, and some door was opened.

It was a sunny, cold spring day on campus, which in Olympia comes reliably, but interspersed with the heavy, cold rains hanging on. The sun warms and settles the chill, sunlight steams off cold rains, leaving the air bursting, like frozen cherry blossoms bulging and shattering as they thaw. I felt free, elated. I felt close to Rob, like we had furthered some sort of purpose from his death. I felt like maybe we could win something, at some point, like maybe some carve out a bowl, a cop-free space of clarity.

I walked back to my car, and looked at my phone. I received a text message that a co-organizer had lost a co-organizer: Eucy, a seattle-based DSA member, to suicide following periods of houselessness and police interactions. I wrote back something that I thought was meaningful– raw, warm but also stilling, then I sat in my car, my bright cloud muddled now, riddled with tiny nails. I put my head back, and drove home completely emptied.

While I believe in public service, as an abolitionist, I still live in a world of constant violence.

Any songs we write, we sing inside an echo chamber of grief, which can make renewal and little gains seem meaningless. In the following weeks I reached out to my co-organizer, M, just as friends and trying to offer support. I promised her I wouldn’t talk about work or organizing. She shared about Eucy’s death, the ways the community were responding and processing. She would make these little pauses and eventually there was a long pause. She had been waiting for me to say something.

“Sorry, I know that’s a lot,” she followed up her own story, sinceI didn’t know how to respond; I’m always better in writing than talking, dysphasia being a constant presence in my life, but I know it wasn’t that. Over my cell, which, in my almost-40 brain should clear out all the imperfections of the landlines of my youth, I could hear clicks of shoes echoing in the hallway where she was sitting, people coming and going from their lunch, walking past her as we spoke. I knew I just felt sad.

We slid into talking about our movie lists: her 90’s lesbo rom coms and my favorite artsy action movies, and then backslid further into talking about work, and, eventually, organizing– even though I promised I wouldn’t. Eventually, M said “Ok, well I should get back to whatever I am being paid to do right now,” and we cordially said our goodbyes, to go back to that traumatizing world.

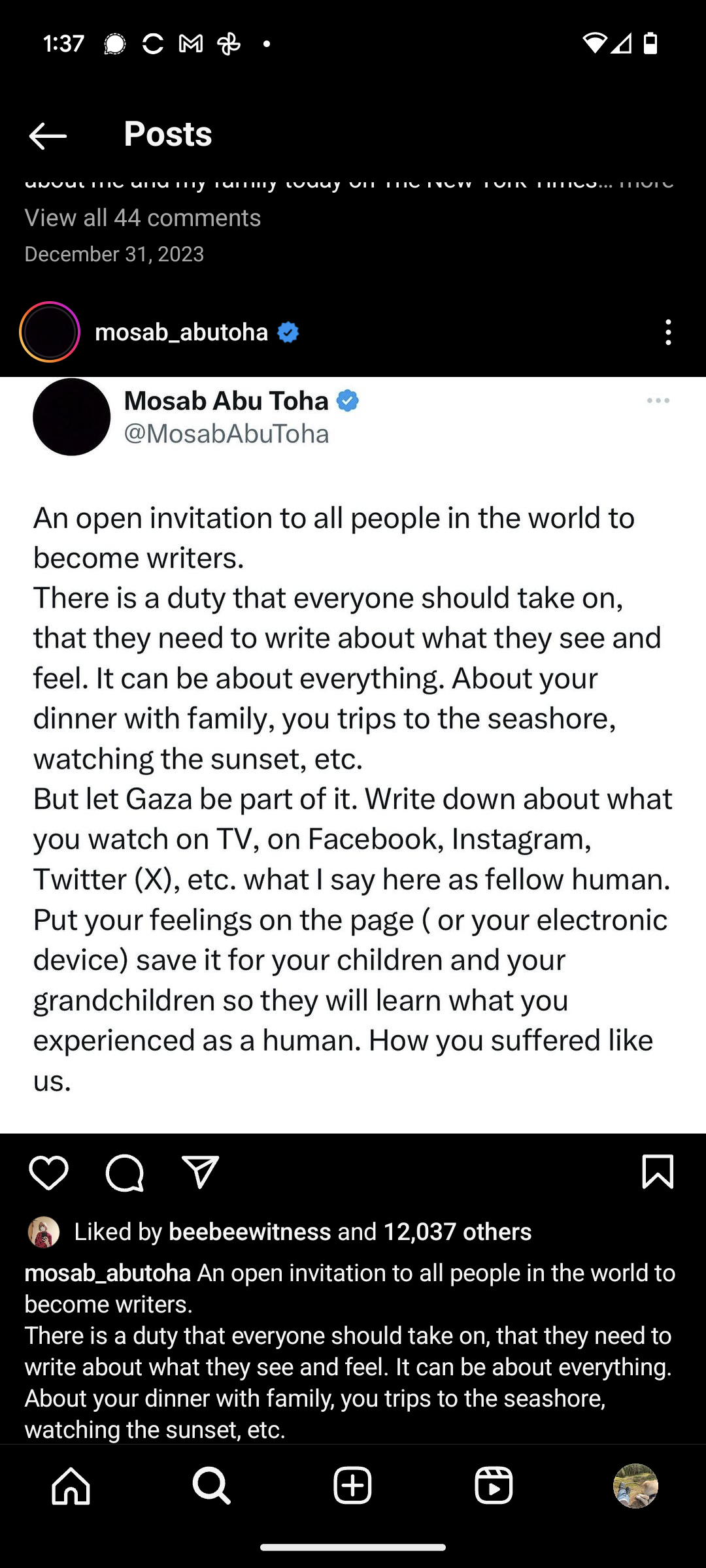

In spite of this failure– to really be there for M, in this thread of our community affected by police violence– I remain curious how I can find, and create, shelter in this world– a shelter that insulates but also pushes back against violent, hierarchical fabric. I want to create writing and art that is accessible, that motivates and metabolizes rather than paralyzes. I want to write stories that spare no details but also give us ground to stand from and lift ourselves from. I hope this piece can be a vehicle for that work, and ultimately I hope that we can realize Lorde’s dreams: of a world without police.